Ali Osborn Observes and Reflects

From October 12 through 15, artists along 14th Street presented alternative spaces or a rethinking of existing spaces. While visiting these sites—watching art being made or discovered—I thought about how each piece posed some challenge to what is expected or anticipated by the public. Everything at Art in Odd Places (AiOP) is outside, but it is also outside norms and preconceptions. Or, as I realized while watching a woman wrapped in flowing silver foil walk at a glacial pace down the sidewalk, the work lives inside some other system of rules or directions that has been temporarily laid on top of the existing code of conduct. But artists don’t give us a lot of answers. So, this secondary system of rules isn’t exactly handed out or explained. Instead, it’s transmitted in gestures and symbols which the public is asked to interpret and decode.

Arantxa Araujo, SENSEsoscope

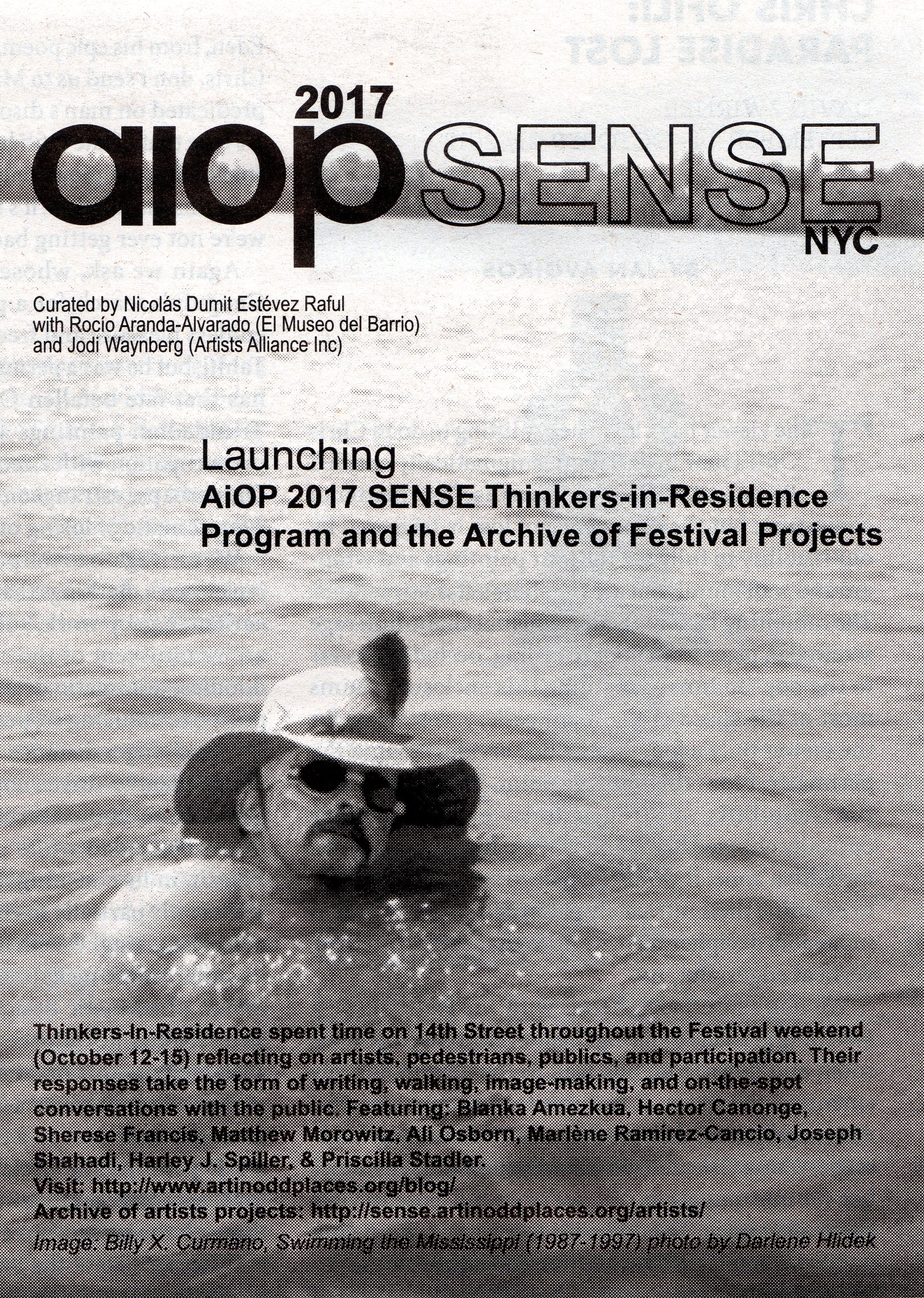

As I puzzled over this and the art on 14th Street that weekend, I remembered a list of directions that does exist in print and points towards how one might begin to make or understand art in a social space: Sister Corita Kent’s Rules and Hints for Students and Teachers. The first item in this list reads, “Find a place you trust and then try trusting it for a while.” This is not something pedestrians are used to doing in New York. They trust the place of the street and sidewalk only insofar as they assume they will get where they’re going at the appointed time if they don’t stop.

Sister Corita Kent, Rules and Hints For Students and Teachers

AiOP artists performed, installed, and shared work that offered potential detours and diversions to passersby, new routes of experience on top of their expected paths. Some of their work functioned as invitations to trust the space of the sidewalk as something more than a place of conveyance. On Friday evening Jan Baracz lay a square of fabric soaked in india ink on the sidewalk and surrounded it with paper plates. Encouraging people to step on the fabric then across the plates, Baracz was calling attention to the way we, and especially our feet, are implicated in the flat refuse of the sidewalk. We author that stuff by dropping it there, and then we sign it with our footprint. Other work played on the idea of the street as a place of movement without interrupting it. Unrolling a red carpet in line with the crosswalk, artist Ayana Evans gave pedestrians the opportunity to be empowered and joyful without missing a beat, or a step toward their destination. With her piece Evans was also presenting a transaction wherein the currency was trust: if you trust me and walk down this red carpet, you will like it.

Jan Baracz, Cosmic Error

Still other work coexisted so uncannily with its surroundings that people passed it by unaware of the presence of art. Hiding in plain sight can be a difficult quality to pull off. Battleships achieve it economically by being painted haze gray—a last line of defense, or offense. I’ve heard of graffiti artists wearing coveralls, and carrying a ladder to pass as legal wall painters. Standing next to his piece If I Could Build Anything I Wanted III, Enrique Figueredo explained that The Home Depot in New York sells gallons of premixed green construction paint. So when he installed his plywood box between 8th and 9th Avenues, a coat of this green paint helped it sit inconspicuously in its surroundings. Just another construction site. But a glance through one of its four rhomboid windows (typical shape and height of those found in “real” construction siding) revealed a different site within.

Ayana Evans, I Want Some Sugar With My S***

In general, the various unexpected moments and experiences presented by these artists remind us of the existence of other possible paths. Some of these paths are slow and meditative— i.e. Arantxa Araujo’s SENSEsoscope. Some paths detour inside, like Enrique Figueredo’s work. Some paths, like Ayana Evans’ I Want Some Sugar With My S***, embody Sister Corita Kent’s ninth rule: “Be happy whenever you can manage it. Enjoy yourself. It’s lighter than you think.”

Enrique Figueredo, If I Could Build Anything I Wanted III