How this cultural vigilante is creating models for controversial conversations we don’t normally have.

Tasha Dougé is up with the sun. For so many who have lived this past year on our own schedules, catching a few extra z’s in the morning might seem like a luxury. But Dougé had already been up for a few hours when she answered the phone at 9am, and was opting out of any warm up questions, “give me what you got. I’m ready for the heavy hitters, just give it to me straight.” The Bronx based artist is no exception to the New York stereotype in that she shares a limited tolerance for nonsense. She needs no warm up or wake up call.

She is the wake up call.

Photo by: Anthony Lewis @neatshinyowl

Her artist bio will tell you that Tasha has been featured in well known publications like The New York Times, Essence magazine and Sugarcane magazine. Her work has appeared nationally at the RISD museum, New York’s Apollo Theatre, the Rush gallery(Philadelphia), and internationally, at the Hygiene Museum in Germany.

But what her social media presence, will tell you is that she isn’t just an artist but a fierce energy force tapped into a higher power available to all but only heard by a few who, like her, are really listening.

“Because my artistry is so aligned in spiritual and ancestral work, there have been so many beautiful ah-ha moments or connections that have led me to be like, Je-sus, ancestors, just text me!”

When deciding to launched her “convHERsations” she didn’t see it as a risk but a calling. “When we speak about risk it always carries this daunting connotation. Instead as artists and humans we need to leave behind the scarcity model and shift into the practice of abundance. Regardless of the risk we take, whether it’s a “yes” or a “no,” we still find ourselves in a different place. We’ve grown. We may gain a connection with someone we didn’t have before, but most importantly we took action. We made an investment in ourselves and engaged our curiosity. If you do that you’re going to have more information on what you need to do next.”

When you look at her art and the underlying themes of her work, this makes sense. Her creative evolution is rooted in this exact mindset. Risk it all for a hint at what comes next. Pounding her tap shoes into the ground at a young age was foreshadowing of the organized chaos that she would soon love to create. Working in the prevention department at a non profit clinic in Harlem would move her to challenge reform models that women have suffered through for ages. Little did she know gazing upon “The Great Wall of Vagina” (Yes, a whole wall. Look it up!) at the vagina festival she attended in 2008 would ignite her artistic practice.

“Working at the clinic, I felt bound by red tape and bombarded by the deliverables being given, it just felt claustrophobic to me. I can hand out condoms all day but what I saw were deeper self esteem issues, suppressed voices and shame. And I just thought, there is a better way to do this. How can we bring information and behavioral change to women in an avant garde way? And, lightbulb…Art!”

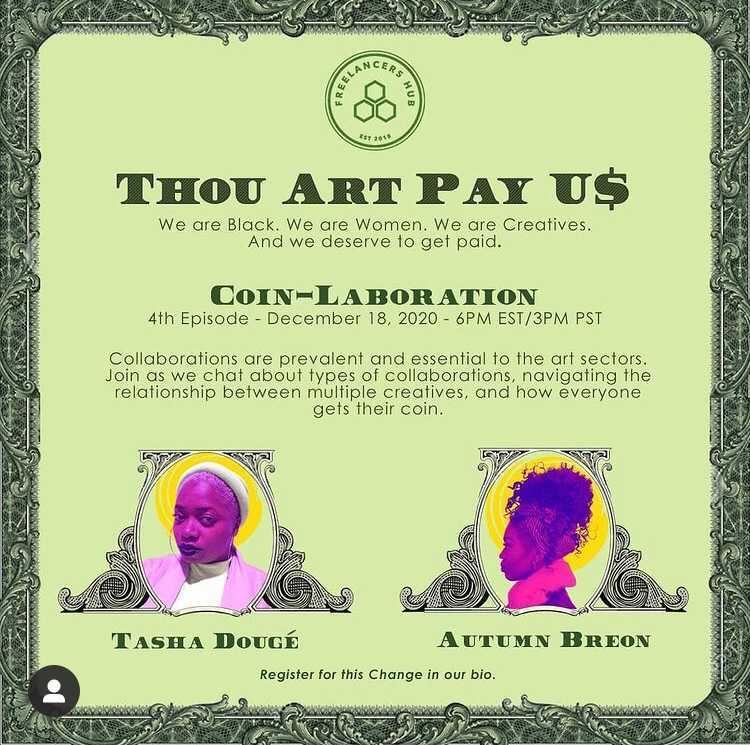

Inspired by her work at the clinic, Dougé launched her exhibition at Chelsea’s Rogue Space Gallery in 2015 and hasn’t stopped since. Her work, though rooted in women’s health evokes pride in the Black experience, speaking to the contributions and hardships experienced throughout history and as modern artists and professionals. “ConvHERsations,” redefines how women feel and see their bodies and has progressed to empower entrepreneurial women of color and their creative journeys.

“Throughout my own artistic process, I’ve always kept the harm reduction model in mind from my time at the clinic. I’d worked places that institute an abstinence model but you can apply hard reduction to any facet of life.”

Initially experienced in the drug use sector, Dougé shared that rather than quitting cold turkey, the harm reduction model allows people to commit to small goals instead of one large hurtle that at first seems unachievable. Dougé says “harm reduction prioritizes the persons agency and at the same time offers alternatives. What I love is theres still humanity attached to this method, you know?”

She’s listening to what’s there and bringing to light what’s not.

When asked about this year’s AiOP’s festival theme: NORMAL, she taps back into the Tasha you might find on Youtube- meditative and introspective. “Normal is a term used to buy into other systems. Being your authentic self should be normalized, but being normal should not.”

Her passions and ambitions have expanded from women’s health, but still remain with redefining what society has told them about who they’re supposed to be or look like with her convHERsation series Thou Art Pay U$. With her hand in so many bags, virtually cultivating her open dialogue series is one of many projects. She is currently an Associated Artist with Culture. But for those looking to get a peek at her work first hand you can find her on instagram @convhersations_ , by subscribing to her Youtube channel, Thou Art Pay U$,and of course along 14th Street in May with AiOP.