If I asked you to close your eyes and describe a New York dive bar, what would it look like? Who’s bellied up to the bar next to you? What daily special is scribbled on the wall? Is it classic rock or top 20 tunes setting the mood from the boxy speakers in the corner? Do I even want to ask what it smells like?

Of course, in the age of Covid, all these answers might be different but for anyone craving a bit of that 2019 normalcy, there’s really only one place to go and that’s East Village Social on St. Marks.

This year will mark the 14th annual festival for Art in Odd Places. And for obvious reasons, our curator, Furusho von Puttkamer has chosen the theme: NORMAL. After the marathon of a year that was anything but normal, it seems appropriate to strangle old ideas and redefine the word in a way that allows creative control. “Throughout the pandemic, I kept hearing people wanting a return to normalcy,” shares Puttkamer. Normal, though, only ever applied to a very narrow group of people in this country: wealthy and white. If you weren’t both of these things, the rules of America apply differently to you. You can be rich, but if you’re not white you still face discrimination. You can be white, but if you’re poor you’ll be facing an uphill battle most of your life. This year’s focus is meant to highlight how restrictive and destructive NORMAL actually is for most people in this country.”

For most of the year we agonized over postponing our festival and watched our mother-borough lose a little bit of the energy that’s always made the Lower East Side vibrational. However, one thing has held constant and kept our team virtually trudging through 2020: our community and the local establishments that surround our long held festival route. Lucky for us that includes a neighbor with reasonably priced drinks.

Only how do you write about a historical artifact like East Village Social or a legend already known by so many? A quick google search told me what I already knew. The only information worth reading would have to come straight from the source. So AiOP sat down with the one person who knows the monument best, Gerard McNamee.

The long time owner of EVS looks exactly how you’d want him to,but Gerard is the kind of guy who might appear different to each person he meets. To his friends at Webster Hall, where he spent a past life as the Director of Operations, he is an expensively suited door lord. To the Authorities, an occasional downtown nuisance. To his family, a die-hard comrad. But to me, emerging from the bar’s ancient basement onto St. Marks, his mask pulled just low enough for his cig to hang out the side of his mouth, he was Rock n’ Roll personified.

He calls out to Jim, from Holyland Market one door down before wandering over to his Harley, Iyana, when I decide to make my move. We find a table over the cellar doors. I order a drink and the conversation quickly moves from the Brazilian women he names his bikes after, to city zip codes, and then eventually, to the topic of the year- Coronavirus.

And it’s then that I understand why Furusho chose East Village Social as our neighbor to highlight. Just like Art in Odd Places, they’re a grassroots gang. Looking around at the sticker covered fort, out front, patrons meet on wobbly bar stools for “Tattoo Tuesday.” On Tuesday’s the deal states that if you have a tattoo, you get a free drink. Just be prepared to show proof, wherever it might be inked. Art enthusiast or not, it’s easy to see the operation is performance art itself. “We’re adapting every day. Everyone is, but it’s sink or swim…so you know,” McNamee pauses for a drag of his smoke and shrugs, “figure it out.”

I find it refreshing to hear New Orleans jazz play in the background while he lists off seven different department agencies that have come to visit the bar since COVID first threw the city into quarantine. I took a chance and guessed they hadn’t come for the drink specials or the ambiance. “We couldn’t play music indoors, so guess what, fuck it, we’ll play music outdoors.” With new limitations in place, McNamee picked up the phone and called “the guys,” who I soon learned to be otherwise known as the East Village All Stars, an alternating music gang led by Smidge Malone.

I take a warm gulp of the hot toddy and feel it move down to my toes. McNamee goes on to describe Smidge as a scrappy gentleman who drinks, stays up for days on end, and screams into his trumpet every chance he gets. At this point, I’m unsurprised to hear the two go way back and oddly jealous that I might not be described as coolly by my friends.

“So check it out,” McNamee jumps to a day in June, following the death of George Floyd. To him, New York, the city where he was raised and reinvented, seemed heavier than ever before. Manhattan had survived the peak of the virus, the looting, the protests, and the politics. “And then it was a nice day, and it was a Friday afternoon,” the pace of his words speeding up, “and the fucking sun came out at 80 degrees, and seven businesses on the block opened up for the first time in a long time, and the band was here that day. It was like a collective sigh of relief. I could get emotional just thinking about it.”

The bar’s Instagram will give you a small glimpse of that day. Tenants hung off their fire escape to listen to Smidge blow his horn, while passers threw money on the curb. Unfortunately, not everyone shares the same appreciation for street jazz. News of the All Stars at EVS had blown it’s way uptown to the Mayor’s office and eventually on to the Governor’s office, who responded directly.

McNamee leans forward with a new cigarette between his fingers and a grin, “We got Five n’ a half million hits, on Twitter.” Up until now there had been a few modest name drops, but this time he was owning it.

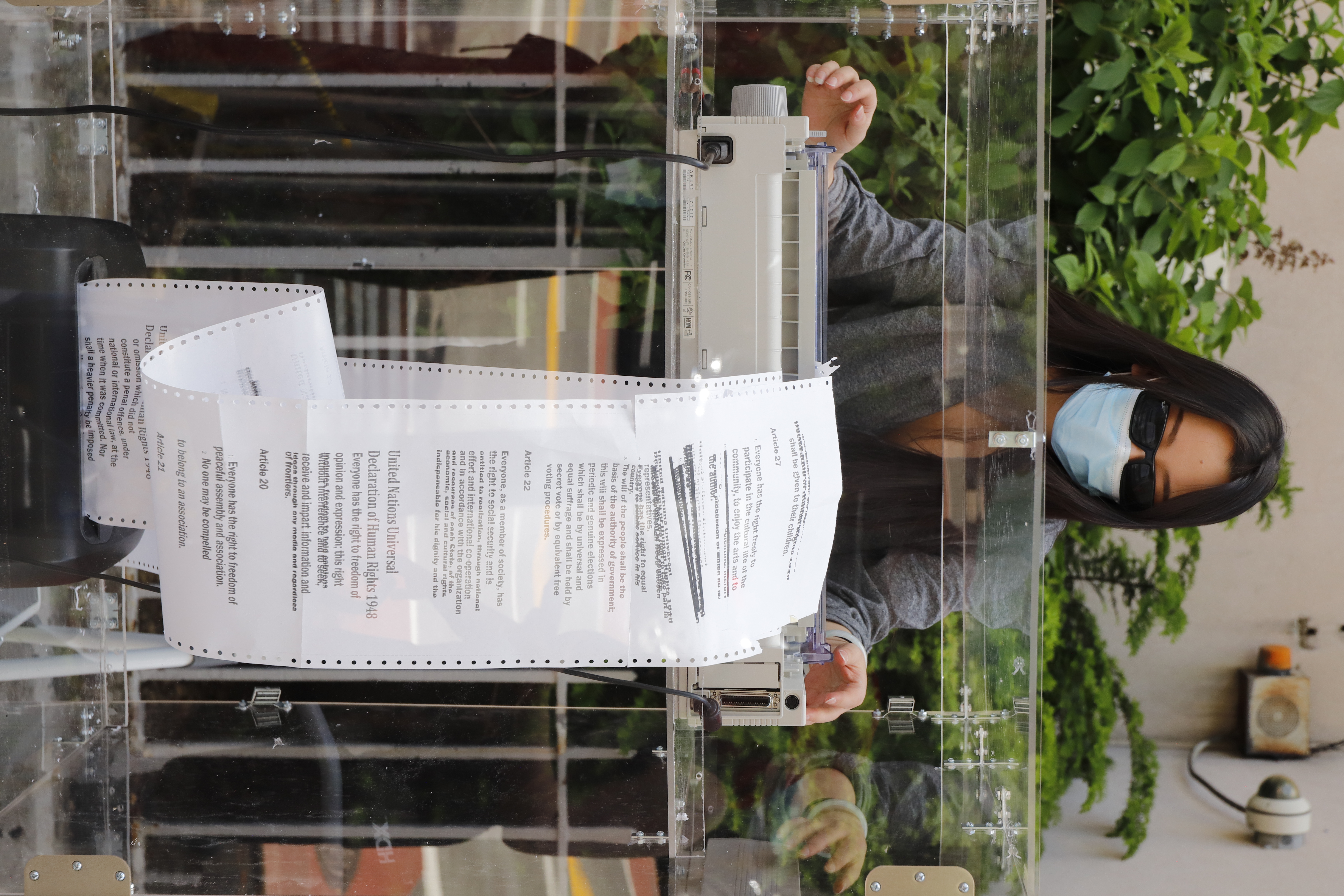

At East Village Social the servers are properly masked, taking orders from behind a plexiglass window, and providing food with each drink. McNamee respects the rules even if he bends a few every now and then. Him and his staff, like all the small businesses in the Lower East side, haven’t had it easy this past year, but he is genuine when giving credit to the city for allowing street seating.

As with most performance art, EVS is learning to finesse their limitations in real time.Their outdoor seating has managed to keep the bar open and it’s employees scheduled throughout quarantine, but the motivation to help the creative community has been an ambition McNamee’s advocated since his days at Webster, where he pioneered the Quarterly Arts Soiree.

Listening to Gerard describe the Q.A.S., I could’ve sworn he was reciting the founding pillars of Art in Odd Places. Our mission, our own beliefs, they pretty much matched word for word. The freedom to create outside of public space regulations has been the propelling force of our organization for 14 years. With this past year being one huge regulation. It’s given our team and our selected artists even more reason to get art on the streets.

Museums, though rich in history and curation, also tend to exhibit a sense of intimidation and privilege that keeps a lot of people from visiting. It keeps a lot of people from learning, from questioning, and from interacting in a space that’s real, messy, and genuine. Because of this, the price of admission for AiOP’s festival has always cost nothing more than sidewalk curiosity.

“This kid that we had up on the walls a while ago was going to throw away his collection of photorealistic paintings of the 27 Club. So I threw them up in the bar and a few weeks later a piece sold for $500. He couldn’t believe it.” Not a bad come up for what would’ve been garbage. “I’m willing to give a platform to anyone who believes they’re the next Basquiat or a rock star. This is all art, art is for everyone.”

I catch myself nodding like I’m at a rock show. I believe wholeheartedly in his words, but I’m also pretty sure I was starting to feel the effects of the third toddy I’d ordered. East Village Social is the last punk bar on the block and perhaps the one with the most heart. It’s a haven for those looking for a place to play their music, hang their art, and shoot the shit with someone at the next table. At a time when we’re all thirsty for a little engagement it’s places like EVS and public art festivals like AiOP where we can catch a glimpse of the old New York. Real, messy, and genuine. For the length of our interview it really is 2019. There’s no coronavirus, no protests, no politics and I don’t want to leave.

I take my last sip while McNamee puts out another cigarette. “Sure, I could be doing other things, landscaping, construction, driving, but this is my life…throwing parties. That’s what we do here every day. We protest sadness and we throw parties.”

I sway on my wobbly stool and silently decide that’s the best way I’ve heard anyone describe a New York dive bar.

Written by: Taylor Ryan

Photo: Angela Liao

Photo: Angela Liao Photo: Noah Herman

Photo: Noah Herman Photo: Noah Herman

Photo: Noah Herman Photo: Bob Krasner

Photo: Bob Krasner Photo: Brian Schutza

Photo: Brian Schutza Photo: Angela Liao

Photo: Angela Liao