By Matthew Morowitz

In our previous feature, AiOP learned who the organizers of the Freedom Harvest Collective were and got a sense of the atmosphere of the space where the #RISEOFTHEDANDELIONS event took place. In this part, we are going to delve deeper into some of the specific works from the event, as well as hear about some of the pieces the Collective found to be the most memorable.

“The Rise of the Dandelions” Video courtesy of Joel Suarez and Gabriel’s Eye Film and Photography.

“We only asked that the audience or community be present and show up for themselves.”- Jasmine Wade

As the public came in and settled themselves, Jasmine began the event by explaining why it was going on, what the Freedom Harvest Collective was hoping to accomplish, and the importance of community:

“I opened the event with intentions by the Freedom Harvest Collective and the participating artists. I began by explaining the symbol of the dandelion; that we are each a dandelion, rising through the concrete of systemic oppression and oppression. Through our struggles we multiply, the self-pollination is our resilience and our roots only grow stronger against the attempts to repress and erase our existence. We are each other’s medicine. We heal together.”

Jas Wade and Rey Fukuda preparing wall installation of a 6 ft Dandelion. On the floor laid markers and folks were asked to write down a wish, hope, prayer for themselves, loved one or community. The dandelion has remained in the space, past the March 9th #Riseofthedandelions event. Photo courtesy of Ashley Blakeney.

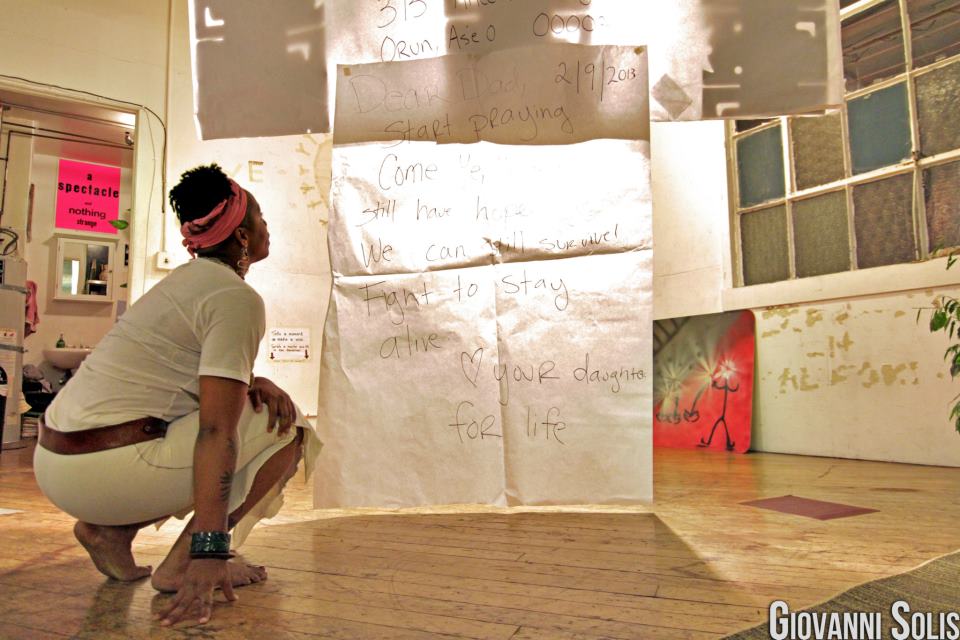

From then on the audience was exposed to and able to interact with a variety of pieces and performances. Once again drawing from her own personal experiences with how sheriff and jail violence impacts families as much as the incarcerated, Patrisse’s piece, titled “Pushing the Envelope,” looked at the letters she and her father would write to each other during his time in prison:

“I did this piece where I basically blow up an envelope of my father’s that shows this letter that was addressed to me and then the stamp that says ‘California state prison’ on it, and then I blow up a letter, the same letter that was in that envelope, I blow it up and create these really big art pieces. Then I created twelve 12-foot envelopes of something that I sent to him and I have that hanging up on the wall for all of these different hangings, and I created a letter to him. The envelope is addressed to the heavens because my father passed away in 2009, he was released from prison in March of 2009 and he died in September of 2009.”

Patrisse Cullors performing “Pushing the Envelope.” Photo courtesy of Giovanni Solis.

The work also served as a way for Patrisse to give more agency to herself and her father, whose relationship was defined by his incarceration, a situation that ultimately contributed to his death.

“I say that him being incarcerated most of his life killed him and I say that [because] folks who are on the inside age and their life span is [over] much earlier than those who are able to live on the outside and a healthy life. This piece is dedicated to him, it’s dedicated to me, it’s kind of like an ode to our relationship and it’s about giving me more agency to say ‘goodbye father and thank you for everything you’ve given me.’ He spent most of his life behind bars, I spent most of my life writing him while he was behind bars, so it was a really powerful piece for us.”

Jermond helped contribute to a piece known as the “Dandelion Song;” this piece will be discussed in greater detail below.

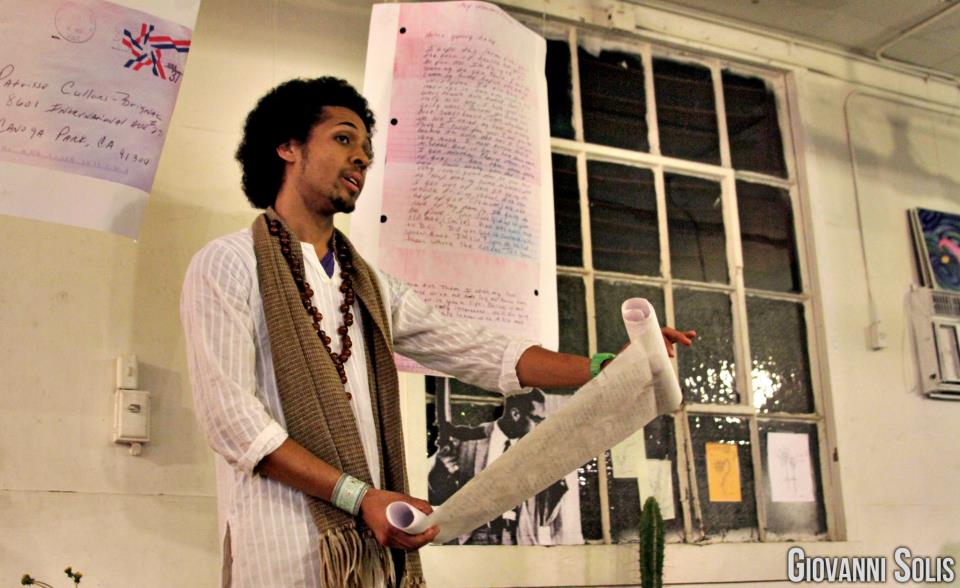

Mark-Anthony Johnson performing “The Crop.” Photo courtesy of Giovanni Solis.

“Through the whole event I also coordinated a performance piece, so I was managing some of that,” recalled Shruti. Her piece, “Seeds Spreading,” which brought together performers from API backgrounds, allowed Shruti to not only highlight ally support towards the issue of jail violence, but also as a way for her to find solidarity on an issue that historically has been targeted at Black and Latino communities:

“I was helping coordinate the performers, we had about ten performers and one of those pieces was a group of folks who identify as API and sort of talking about our narratives connecting to state violence and state violence effects on our families and communities. I wanted to shift the stories about how our identities related to the prison industrial complex, so we all wrote stories on reclaiming a piece of history that we didn’t know about in relation to state violence, or a moment of solidarity with a black or brown person. For myself I wrote about not knowing history and feeling like I was lost in history, not knowing why my family was in this country for so long, because I never learned black history growing up.”

Haewon Asfaw, Almas Haider, Jessica Gonji Lee and Shruti Purkayastha performing “Seeds Spreading.” Photo courtesy of Ashley Blakeney.

Gonji, whose piece was connected with Shruti’s, as they were part of a 4-womyn collective, drew from the history of U.S. military involvement in Korea in order to create a dialogue between the global U.S. Military Industrial Complex and the tactics adopted by the police on marginalized peoples and oppressed nationalities domestically:

“My specific contribution was a collaboration amongst queer API women utilizing movement, spoken word, music and [Theater of the Oppressed] to affirm our commitment as allies to Black and Brown people, as well as to bring in our intersectional experiences with state violence as APIs. My piece paid tribute to the Korean men in my life who fell victim to the state in the many forms of violence that it inflicts upon Third World peoples. It was an opportunity for me to explore how US Imperialism operates through the Military Industrial Complex in the Korean peninsula at the expense of the Korean people’s sovereignty, while the police within the US utilize much of the same military tactics to target oppressed nationalities living within its borders.”

Patrisse Cullors standing inside of family installation, which included letters between herself and her father and a cut-out of Malcom X in the window that provokes feelings of protection for our families and communities under attack by the state. Photo courtesy of Ashley Blakeney.

Along with opening the event, Jasmine also partnered with Patrisse on an installation that looked at the impacts of state violence and mass incarceration on the family. Incorporating Patrisse’s “Pushing the Envelope,” this installation brought in elements related to Black history, slavery, and, colonialism in order to make the personal experience universal and to universalize the personal. The installed space was meant to reinforce the theme of strength found in unity and love, the ideas behind the event and needed to reclaim dignity and power in the face of the prison industrial complex.

“We rolled out a huge carpet with plants placed at each corner, a family table and chair, set with plates and dandelion tea, a cut out of the famous picture of Malcom X keeping watch outside of the window, letters written between father and child blown up and a huge dandelion installed on wall, asking people to write out their freedom dreams, what they wish for themselves and their community. I was inspired to set up a familial place, a space that connected people to their homes and family, and that each performance shared would be received in that context of love and accountability to each other and our loved ones. This installation was rooted in the history of family separation from slavery and colonization to mass incarceration and forced migration. We wanted to bring the family together, to acknowledge the loss and separation, while at the same time filling the space with love and protection to feel. Audre Lorde says, ‘I feel, therefore I can be free.’ The family installation was set up to speak directly to people’s hearts, hold them in firm, tender hands, and begin the feeling towards freedom, without shame, guilt or fear.”

“The moment that I remember the most vividly was when people rushed to embrace one another, laughing and crying at the same time as soon as the program ended.” –Gonji Lee

While the entire event demonstrated the kinds of emotions and ideas the Collective wanted to get across, for each of the members specific works stuck out and struck them on different personal levels. Yet while all of the members of the Collective had their own particular preferences, across the board they were almost all in agreement about the impact two specific works had on all of them: Mark Anthony Jonathan’s “The Crop,” and Jermond Davis and Rey Fukuda’s “Dandelion Song.” The former, a spoken word piece “never fails to send chills down my back,” as Gonji describes it. “He crafted a manifesto for the prison abolition movement in LA that speaks to the realities of mass incarceration and the [Prison Industrial Complex] in an unashamed fashion.”

According to Jermond, the “Dandelion Song” was “a song performance… which consisted of rhyme, rhythm, vocals and a guitar expressing freedom harvest artistry.” Jasmine describes the song as “one of healing and awakening” and “definitely one of our generation’s freedom songs,” a sentiment echoed by the other members of the Collective.

Jermond Davis and Rey Fukuda performing song “Dandelion” inside Ancestry Installation. Photo courtesy of Ashley Blakeney.

Another piece that stuck out in Jasmine’s mind was a performance of “storytelling and movement” by artist Three Breazell set to Frank Ocean’s “Crack Rock:”

“Three’s dance performance to “Crack Rock” embodied the War on Drugs, which is responsible for the ballooning of prison and jails populations; 2.4 million black and brown people are incarcerated in US jails and prisons. Los Angeles is the largest jailer in the world, here in Los Angeles; we live in one of the biggest police states. For California, nearly 60% of people who are incarcerated in state prisons are from Los Angeles County. The four womyn collective was powerful because performing from the ancestral installation, they all spoke against the historical amnesia that the system feeds on, and each artist in their sharing showed solidarity with the black struggle and the struggle against state violence and mass incarceration. Their piece represented the international movements against US occupation and violence, while also bringing in the spirits of loved ones who are incarcerated.”

“The Crop By Mark Anthony Johnson” Video courtesy of Gabriel’s Eye Film and Photography.

Patrisse, who was also impressed by the performative “The Crop” and “Dandelion Song,” also found that a third piece, a multimedia mashup, had a large impact on her:

“…a good friend of mine, Eden Jeffries, created a mashup for RISEOFTHEDANDELIONS in which she uses Angela Davis old footage and Storyboard P pieces [Storyboard P is a New York Based artist and dancer], and artists there in NY. She’s a dancer in NY, she just did this powerful piece, she created this mashup of beautiful music, his [Storyboard P] dancing, and Angela Davis and dandelions and that was pure gorgeousness.”

“Rise of the Dandelions” Video courtesy of Eden Jeffries with Angela Davis and StoryBoard.

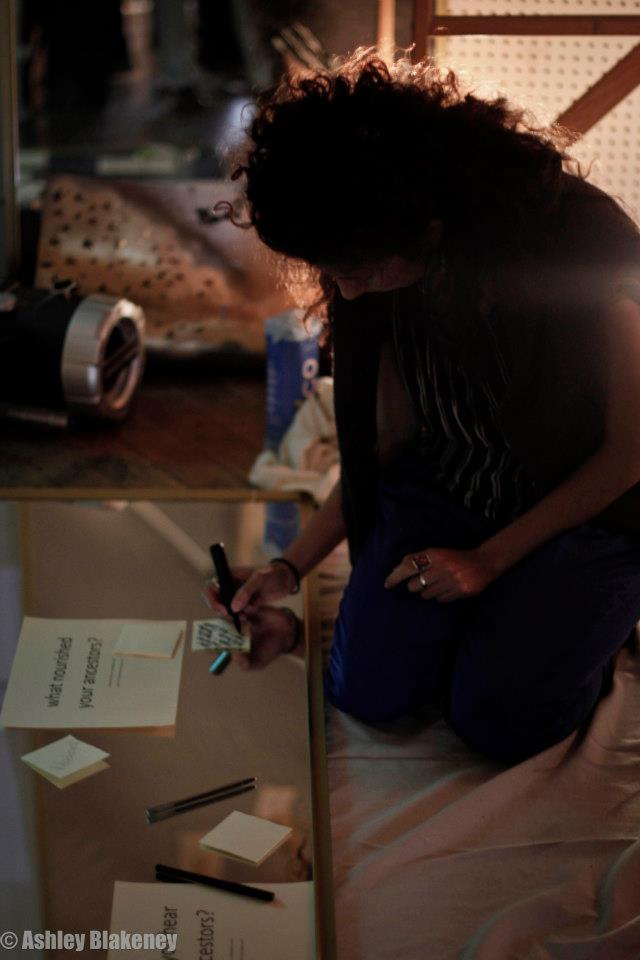

Shruti found an interactive piece involving a mirror and the stories of everyone who attended, had a profound effect on her understanding of how personal histories helped create a sense of place in the present by connecting with the past:

“The Deep Roots installation incorporated 3 elements, an altar space with found objects, including a sculptural interpretation of a dandelion. A dandelion made of recycled material depicting an arm/strong stem grasping a heart growing from the dirt. Nearby, hanging from a canopy, was a 4 foot canvas with a broad stroke painting of roots, one side goldenrod tones, and the other red purple blue blood tones. Both of these pieces were created by Southern California visual artist Yoyo Negrete…I think the most engaging, impactful part of the installation was we placed a mirror on the ground and placed different questions about people’s ancestors. This was meant to be an interactive piece so we put post-it notes and pens for folks to reply to these questions on. Basically we talked about where are your ancestors from, how did they live, what nourished them, how did your ancestors heal, to just have this kind of a spiritual space for folks to call on their ancestors into this space and think about our roots, countering this historical amnesia through this piece of reflection and sharing. I think almost everybody who was in this space interacted with this piece and wrote different post-it notes based on these questions and we had some really great responses; some were really detailed, like ‘my family is from this particular point, which is now called this city and it used to be called this’ and it had this whole history written out, and some which were much more general like ‘I don’t really know where my ancestors are from, but I know they are from or probably from this region of Africa or this region of India.’ It was great in terms of just having that moment to share history in a way that’s not so constructed.”

Community member contributing the Ancestry Installation, answering the question: “what nourished your ancestors?” Art work inside the Ancestry Installation were created by Yoyo Negrete. Photo courtesy of Ashley Blakeney.

Yet for Shruti, the most important part of this whole exhibition was how it brought many different groups and people together to create a collectivized experience based around the art and the message:

“All of these pieces we’ve talked about as a group and really supported each other, we worked very collectively in putting everything together. It was a lot of group and collective ownership over the process. To me the process oriented art is really important; not so much how beautiful is my project going to be but how connected is our process right now and how are we really sharing our stories and creating the sort of narrative to provide a different kind of history than is out there or than is supported in the mainstream.”

The community, audience, participants sharing reflections after the program. Photo courtesy of Ashley Blakeney.

As for Gonji, it was the message that she took from the whole experience that really stuck out for her:

“The room was buzzing with people sharing more stories and proclaiming how their spirits were moved. One thing was as clear as ever in that moment, we need to take the PIC down, and we’re ready to do it NOW.”

In this part, we discussed the specific projects created by the Freedom Harvest Collective members and the works that stuck out them. Be sure to stay tuned for part three where we will look at the dialogues that were created from this event, as well as what the future will hold for the #RISEOFTHEDANDELIONS.