Revaluing Values by Lauren Swayne Barthold

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche extolled the importance of revaluing our values. Rather than take values as universal, timeless truths that are neatly handed down from tradition, Nietzsche proclaimed that the work of being human is to re-create or create our own values. I thought of Nietzsche when I read an article by the Italian theorist Silvia Federici handed-out by No Wave Performance Task Force’s “Flower Kart” at Art in Odd Places 2018 NYC event. Discussing what creates lasting social change, Federici claims that successful feminist “strategies cannot produce lasting change if they are not accompanied by a process of revaluation of the position of women and of the reproductive activities they contribute to their families and communities.” What united the most powerful performances I witnessed over this weekend was their ability to help us revalue our values about the meaning and power of women and female bodies. Laws, while crucial, are not enough to overcome patriarchy. We need to revalue the misogynistic values that permeate our culture as a whole.

Performance art, when done well, embodies elements of both activism and art. Unlike activism per se, it does not insist on what one should do. Rather, it reveals current, often hidden, values, and invites us to revalue them. In this way, performance art is more about the raising of questions that require each of us to struggle to work out a life-long answer and to create our own values. Questions like “who am I?” “Who are we?” and “Who do we want to be?” are raised via performances.

In addition to distributing academic texts (also on offer were a chapter from Susan Brownmiller’s 1975 classic, Against our Will: Men, Women, and Rape and a bell hooks article, “Understanding Patriarchy”), the “Flower Kart” was also handing out free samples of the “morning after pill,” Plan B, as well as giving away two medical abortions, which were composed of four pills containing herbal abortifacients available legally only outside of the US. I took this as an act of not only kindness in this moment where the possibility of overturning Roe v. Wade is increasing, but also hope. For, if the laws change, I can envision “Flower Karts” travelling streets all over this country. (I asked them if they had any plans to go to Texas in the near future where abortion is no longer covered under standard health insurance plans and that nearly 1 million reproductive-age women live more than 150 miles from abortion clinics. )

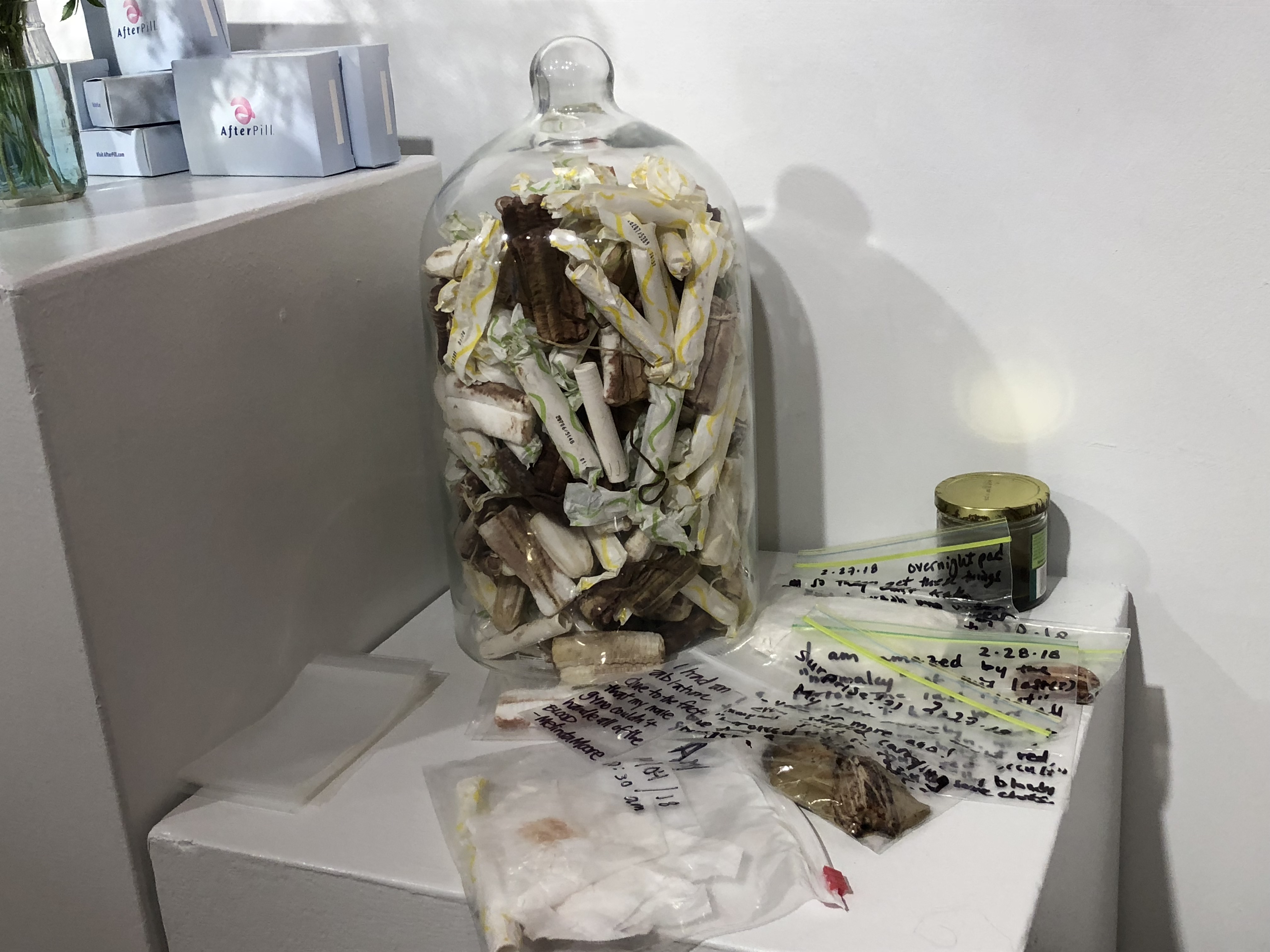

This performance by Amy Finkbeiner and Christen Clifford, which included a gallery installation, was remarkable for its timeliness in another way. As part of their display at the Westbeth Gallery were jars of used tampons, vials of menstrual blood, and gold painted impressions of vaginas, labia, clitorises, and anuses. Rendering women invisible and silencing them are two ways of oppressing women that were on display in the recent “hearing-as-spectacle” of now Supreme Court Justice, Brett Kavanaugh. The testimony of Dr. Kristen Blasey-Ford in the week just prior to this exhibition helped to begin to expose the centuries old misogyny operating to keep women “in their places.” Blasey-Ford’s brave appearance helped uncover, at least for those who have eyes to see, misogynistic values that prevent women from being seen, heard and taken seriously as fully agential human beings. Of course, women, like children, may be seen—but only in so far as they remain beautiful, silent objects, docile and submissive to the needs and desires of the patriarchy. If the female body is not beautiful, not able to be exploited and used by men’s hands, gaze, and penises, then it should be ignored and silenced, at best, and abused and ridiculed, at worst.

How relevant this exhibition was, then, in exposing and celebrating the parts of the female body that cannot easily be seen. The gold-painted material impressions of vaginas, labia and clitorises bring to light and celebrate what has been the “object” of hiddenness and shame for so long and made me reflect upon how the hiddenness of our “private parts” services patriarchy. While some might wonder what the difference is between the attempts by some canonical male artists to objectify female bodies-as-parts and the gold impressions of female genitalia on display in this exhibit, I found the difference striking and powerful. Yes, these are female body parts and not themselves indicative of full agency, but the performance of bringing them into view invites us to consider why female body parts so often go unnamed and unseen? Perhaps more importantly, we are invited to consider what happens when they are made visible and celebrated. Such revealing is aimed to promote women’s agency and not to reduce them to sexualized objects. What is unable to be spoken about remains a source of shame. No-one is embarrassed to stand around and admire the statues of muscled, masculine, male bodies. But how is one to comport oneself in the presence of an impression of a woman’s vagina? Or vials of menstrual blood? And why is the visceral reaction to the latter often one of disgust when such blood is literally the blood of life? Why do we cherish the sanitized new baby but not the processes and fluids that go with it and the powerful woman who makes it possible? Why do we have laws that insist that the pregnant female body is an incubator to be utilized, shut down and opened up at will, in service of the patriarchy?

In aiding us to revalue our values, such performance art is often disturbing, jarring, perplexing, empowering, celebrational. What I didn’t expect to find motivating some of the performances, though, was kindness. Not exactly a value one might associate with the Nietzschean endeavor. Why is kindness often considered a banal, weak, and insufficient value, and one not befitting of art? Art should be edgy, make us feel uncomfortable. . . yet that is actually what I was when, strolling down 14th street, I was asked by performance artist LuLu LoLo if I would like to sit in a chair she was carrying on her back for her performance, “A Seat for the Elderly: The Invisible Generation.” At first, I was taken aback and certainly made uncomfortable given that I don’t consider myself, and certainly hoped others don’t perceive me as, elderly. But why? My own embarrassment and discomfort forced me to reflect upon whether my fear of being considered elderly was not an effect of the very values she was seeking to upend. Of course I don’t want to be “seen” as elderly (who does–right??) if to be elderly is to be rendered invisible or possessing a non-fully abled (i.e., muscled and masculine) body. When talking about her work, LoLo also said that part of what motivated her was to offer an act of kindness. NYC can be an extremely physically demanding place that expects all who wander there to possess vigorous, abled bodies. Refusing to have working elevators or escalators (to name just one treachery of NYC life) is a way of rendering non-existent people who cannot climb stairs. But can art be offered in service of kindness in a way that also beckons us to revalue our values? Perhaps if we feel that kindness has no place in feminist revaluations, then that is because we have not yet allowed ourselves to encounter the fully robust agency of women, which requires a celebration of all the plethora of parts and powers of the female body.

Silvia Federici, Witches, Witch-Hunting and Women. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2018; p. 57. I also love Federici’s revaluing of Nietzsche’s own values in so far as he was a misogyinist!

https://www.aclutx.org/en/know-you-rights/abortion-in-texas

Lauren Swayne Barthold teaches philosophy and peace studies at Endicott College. She is also Program Developer for the Heathmere Center for Cultural Engagement. For more information see https://laurenswaynebarthold.wordpress.com