Looking back at Art in Odd Places RECALL at Year’s End: Of Memory and Legibility on 14th Street

On an unseasonably warm Sunday this past October (as all Sundays now seem to be) I set out along 14th Street, the longest East-West running street in Manhattan, to see just how much the area had changed since the last iteration of the Art and Odd Places festival, which I had co-curated with Juliana Driever in 2014. I don’t generally have the occasion to walk the entire length of the corridor. Art in Odd Places, the unpermitted and spontaneous collaborative festival of public art that artist, performer, and cultural impresario Ed Woodham has produced now for the past 11 years, has given me just such an occasion and a reason to engage with 14th Street as a place, once per year.

This year, for the festival’s 11th Anniversary, Woodham invited co-curators Sara Reisman, Artistic Director for the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, and Kendal Henry, Director of NYC’s Percent for Art Program, to organize a program around the theme of “RECALL.” As with each iteration of the festival, the theme speaks as much to the selection of artists and works as it is does to the nature of 14th Street as a site and a place itself. As sections of 14th Street are practically unrecognizable from what they were just one year ago, RECALL suggests a looking back through eleven years of the festival’s engagement with a constantly changing site.

For the 2014 festival, Juliana Driever and I curated a grouping of roughly 70 artist and collaborative projects on the theme of FREE. In our curatorial statement we were already recalling an earlier New York and earlier 14th Streets, reflecting on the changes that were and are taking place in the city, and responding to a feeling of loss as much to an almost innumerable editorials and thought pieces circulating at the time.

In our curatorial statement, we brought to mind a certain recent history of New York City, at least as it is imagined:

“The 1970s Warriors-era New York City lives in the imaginations of many as the kind of town it used to be. That gritty, wild, at times dangerous place was also a site of agency and possibility. The New York City of present day is much more polished, and encumbered by big money than recent decades; a statement not meaning to invoke nostalgia for the way things used to be, but as a simple point of fact. New York City has changed. Chain retailers (and their shoppers), real estate developers (and their high-paying tenants), and cultural tourists (and their transient economy) now rule the landscape. Between private corporations and city-mandated public space regulations, our every move is watched, recorded, policed, and normalized. Patti Smith said it. David Byrne said it. New York City is not a place for artists.”

At the same time, we asked if New York had really changed all that much:

“Sure, money has moved in. But have the people stopped responding? Has creativity simply dried up? Or, like the city itself, has it just changed? Shape-shifted and transgressed the usual models into more inter-disciplinary, life-specific, and self-directed contexts?” “

In recalling the “gritty, wild” and “dangerous” New York we posited that at least Art in Odd Places existed as a project that sought to open the city up again to the kind of anarchic, freewheeling creative production that (some imagined) existed at a given point in time, and had since subsided. We hoped to respond to the shared sense that something had been lost in the process of making New York “safer” and “cleaner” and even more “bike friendly,” while inquiring whether, as New York became the (second?) most costly city in North America, our freedoms hadn’t also been restrained.

What was being recalled this year along 14th Street? Henry and Reisman were asked to select artists who had presented in the festival in past years – and to work with them either to reproduce what had already been shown/performed/enacted or else to create something new. The sense of déjà vu was palpable, and as the gloss of “the new” often trumps quality in art, not to mention duration and longterm engagement with a site, it was refreshing to see artists asked to re-engage with a site, to re-call it, and perhaps to respond to what had changed since they first created their work.

There is something particular about 14th Street. In a city where, as the old cliché goes, “change is the only constant,” 14th Street exhibits this constant flux more than most streets. Over the years that I have known it (roughly 15 since I first came to stay at a friend’s S.R.O. on the corner of 7th Avenue and 14th Street in my first weeks in the city), 14th Street has never been the same on two different days. Perhaps this is because 14th Street lacks a unified identity, or because, as it runs along Manhattan’s widest point, it is not easy to survey its entirety in one day. Walking from one end to the other will take you an hour, without necessarily rewarding you with the sense of having “gotten anywhere” really.

One might argue that 14th Street is actually a street that asks to be forgotten. Overshadowed by its more characteristic neighboring quarters – Gramercy, the Villages, Stuy-Town, Alphabet City, the Meatpacking District, Chelsea – the unifying principle is that there is no unifying principle. In being the dividing line between such distinctive neighborhoods, it is rendered, by comparison, quite indistinct. For many, 14th Street is not a neighborhood in and of itself, even if people do live and work there. It is thoroughfare, a classic nonplace, a space you may enter only to catch the subway, cheat an underground connection, or that you might cross to get “somewhere” else. Why should it have its own identity? If anything, its nonidentity renders it distinct, allows it to stand apart in a city already brimming with characteristic streets, blocks, and neighborhoods. It shirks any sense of having a distinct character. It is not a “garment district” or a “diamond district” or a “flower district” either. It is not an artsy neighborhood or a hipster neighborhood or a working class neighborhood or an ethnic neighborhood. It is barely a shopping street, even though it is lined with stores. Or perhaps it is all these things, in equal parts.

I lived for a short time on 14th Street in the mid-2000s. From the back window of my rent-controlled, single room occupancy apartment, I looked squarely out into the West Village in all of its bucolic otherness. I could glimpse trees and even a carriage house in the buildings down below that shared the block with my own. From the front side of the building, which I only glimpsed once from a neighbor’s apartment, everything was transit and commerce, bustle and noise, as if I was looking into the heart of the city, which some might say it is. I sat on a folding chair in front of my building one evening for several hours, reflecting on the fact that almost nobody else seemed to stop, much less sit, on 14th Street aside from houseless individuals waiting at the Salvation Army down the street at all hours of the day and night and shop employees out on smoke breaks.

In the intervening years, the building next door (also a S.R.O.) was left to fall into disrepair, until it literally fell into the street. Its population of primarily low-income senior citizens was forced out into the cold one winter morning. The building was pulled down in such a way that for a moment it seemed my old building might next meet the same fate. From an old neighbor, I learned that the tenants had successfully organized to demand basic infrastructural maintenance, and the building still manages to remain standing, if tenuously, today. Clearly the owners would like nothing more than to tear it down so they can sell the land to a developer who will put an empty storefront downstairs and 30 stories of “luxury” apartments above. In the empty lot next door, site of former neighbors’ homes, a falafel truck thought to set up a sort of outdoor restaurant for a year, until the city health department informed the owner that this actually wouldn’t be possible in the New York City of 2015.

Former site of S.R.O. and HabibisNYC. Missing buildings and houseless sleepers.

Living along 14th Street, and walking there now, I have continually been perplexed by how hard it is at times to distinguish one block from the next. This is increasingly the case as empty storefronts replace mom and pop businesses, or glassy towers replace formerly characteristic buildings. This year, too. In part because it seems that everything is possible, this year I was hugely dismayed and instantly cast into a state of depression to see that Rags-a-Go-Go, the stalwart supporter of Art in Odd Places, had closed its doors.

Not the site of Rags-A-Go-Go.

Except, of course, that it hadn’t. Rags was still there, on the next block over, where it had always been. Right next to New Oxford Cleaners, who had mysteriously started to offer “Organic Cleaning” recently, no doubt in an attempt to fit in with the new culture and in the hopes that they too might be passed over by the dark angel of displacement. Hopefully Rags too will be selling organic friperies alongside its vintage leather boots and thus ensure its place in the landscape for another term.

Longtime site of Rags-A-Go-Go. Still in business.

Holding space, like holding time, is a privilege not to be enjoyed equally by all. There is another side to this forgetting along 14th Street. If it is easy to forget what is or was where, and difficult to think of 14th Street as having a distinct identity, it is all the easier to reimagine 14th Street as a tabula rasa, upon which any new fad or fleeting (and generally bad) idea of urban development can take hold. Here we might finally understand how 14th Street, at least the portion running West from Union Square, is slated to be converted into the luxury onramp onto the High Line – or so the spread of von Furstenberg’s Meatpacking shops down the Western Corridor would seem to portend. The newly sprouting glass towers on the street’s Eastern Edge are, meanwhile, undergoing that ultimate gesture of turning a living and breathing city into a starchitect’s rendering and the mallification of even nature itself. How many banks and Duane Reades does 14th Street need? These two gentrifying forces – fashion and real estate – portend a crash of metal and steel and patent leather somewhere around Union Square, Manhattan’s social center. Through successive waves of “improvement” beginning in 1984 with the formation of the Union Square Partnership BID (Business Improvement District), even the park’s original restaurant gentrifier Union Square Café (owned by Shake Shack’s Danny Meyer) claims to no longer be able to “afford” to keep serving its $18 hamburgers and must relocate to “the other side of the park.” What is 14th Street coming to when even overpriced restaurants are being priced out? And what about those who live on 14th Street now, who might, in spite of its not being formally described as a neighborhood, consider it as such? Then again, perhaps this is why a festival like Art in Odd Places can seem so at home here. It is the perfect field for experimentation, risk, and already is actively reimagining itself.

Jabari Owens-Bailey and Tré Chandler, with Nigrum Paenitentiam — When Oprah Wept (2014 edition) performed along a three block area around Union Square West.

The ambiguity around the identity of 14th Street transfers to the ambiguity of the various artistic practices enacted each year for Art in Odd Places. The festival itself tends toward illegibility, or plays on the division between legible and illegible, as it encourages art to engage directly with everyday life, in ways that don’t always look like art. In any “normal” context, the performances and installations that grace the festival each year would stand out as “art.” In a gallery or theater context, of course they would as well. And potentially on some other street, a street more turned toward spectacle (say, 42nd Street) or any commercial or residential street, this charming annual festival would read as a Festival. On 14th Street, on the other hand, the festival can be read variously as: just part of the fabric of the street, an arts and performance event, a spontaneous outpouring of creative energy, a protest, civil disobedience, a miracle, a riot, a police action, a terror plot. What I have noticed in several years of attending the festival is that it brings out the performative aspect of the street itself, where it turns out every third person is already clearly engaged in some form of public performance, no matter how slight that may be.

Stefanie Lynx Weber & Co. perform AUTO MOBILE BODY WORKS behind Pedro Albizu Campos Plaza in 2014.

Of course, this question of legibility varies by the individuals and communities that enter into the space. The question of “is this part of the festival or is this just everyday life?” might not exist as much for those who spend every day walking along 14th Street, who have come to know just what it holds and what it doesn’t, or for others who have come to recognize the festival each year. You might overhear someone say: ‘Oh it’s this again,’ clearly a mark of someone who knows the difference between the everyday thoroughfare and what happens there once a year. Such was a report by Chad Laird, an artist who produced and presented a sound installation with his band JANTAR for the East End of 14th Street in 2014, and represented it there this year.

JANTAR’s piece was modeled on the soundtrack to Taxi Driver, and was played from a concealed speaker to passersby, an homage to a moment and site of New York City that has disappeared. The heavy yet sedate tones filtered ominously over a vacant lot, currently under development, where the infamous bar The Blarney Cove once stood. The Blarney Cove was Old New York at its core, and a neighborhood fixture. The now-destroyed buildings nearby housed other neighborhood fixtures – discount food stores, clothing stores, cheap appliance stores – things that local residents in the Campos houses might want or need on a daily basis. JANTAR insinuates that perhaps this is why 14th Street no longer behaves like a neighborhood – a neighborhood has a need for neighborhood fixtures. When these get replaced by chain stores, banks, and luxury boutiques, the neighborhood as it was ceases to have a reason to exist.

@vrbnks A video posted by Dylan Gauthier (@dgoats) on

Chad Laird of JANTAR, presenting JANTAR’S Eight Spaces of Empty Place, a series of variations on Bernard Herrmann’s score for the 1976 film Taxi Driver, set on the site of the former Blarney Cove, in 2014.

JANTAR’S Eight Spaces of Empty Place, a series of variations on Bernard Herrmann’s score for the 1976 film Taxi Driver, set on the site of the former Blarney Cove, in 2014.

Detail of JANTAR’S TAXI DRIVER installation at the corner of Avenue B and 14th Street this year.

The question of legibility goes along with the question of audience. Who is the audience for Art in Odd Places? There is no ticketed entry. No price of admission, and also, as the festival occurs in public space, no consent required. The works and performances on display are varied enough that between them, there is an opportunity for the transcendence of class and education and race and cultural values. Unlike most art exhibitions in the city, there is no need to “know about art” to see what is happening on 14th Street. E-Team, for example, whose non-art-piece perhaps resonates more with the quasi-academic discussions of art and labor – for example, just how much should an artist do when the artist is working for free – still function within the context of the festival as an approachable proposition.

Looking back over my photographs, I had to consult with the online guide at several turns to decide if what I had seen was in fact an artwork or an everyday occurrence, or both.

All of my AiOP photographs, 2014 & 2015.

This is a familiar feeling, too. Where every appearance of what might or might not be art posits a question. For instance: were the dogs who appeared to be driving a shiny green convertible up and down 14th Street, circling several times around Union Square before disappearing, a performance piece, or a random occurrence? At the very least, their owner has a good sense of the performative, and a keen sense of timing in deciding to drive down 14th Street today.

Unknown artist/human, Untitled (Dogs in green convertible on 14th Street), 2015.

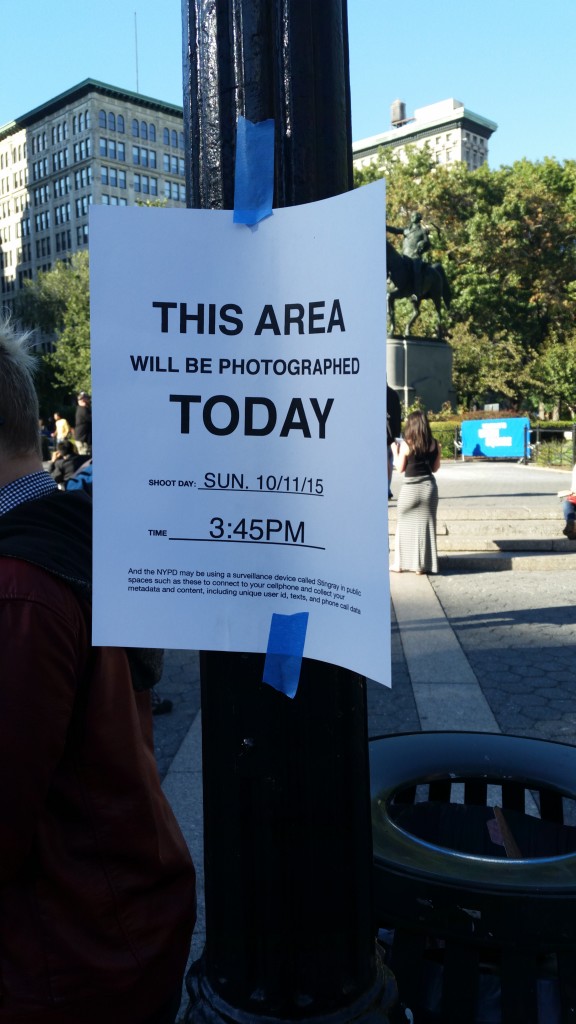

Was the NYPD photographing Union Square at 3:45 pm? It sounded plausible, but why 3:45 pm in particular? (And why had they bothered putting up signs if they were, when they can most definitely monitor the area from dozens of undisclosed surveillance cameras at any time of the day?) And did the orange tape on the ground have something to do with this incursion?

Laura Napier’s This area will be photographed (reprised from 2009).

Who was this woman sitting with wet newspaper on her face, apparently selling bags of rice and beans for several thousand dollars apiece? Was this a performance or a disturbing sign of the times (or both)?

Allicia Grullón, Revealing New York: The Disappearance of Other. “Looking at displacement in NYC and what it means for cities’ diversity and viability. In a time when austerity rules the economic framework in order to deal with corporate and government missteps, this piece looks at the measures a person must take to continue living in NYC or other major international cities.”

I encountered two performances seemingly being staged in unison at two opposite ends of Union Square Park. In the first, a man pleads with a traffic cop/fascist/authority figure/overseer to give him back his clothes. Onlookers post images on Instagram.

Lawrence Graham-Brown, Game: Hunt, Capture, Kill, a “two-hour ritualistic performance draws on themes of liberation, race, and sex while dis-empowering the spirit of Thomas Rice—otherwise called Jim Crow Rice—the father of American minstrelsy theater who contrived to flatter contemporary belief in white supremacy and who was born on the Lower East Side of NYC.”

Unknown performer/human and textile.

In the second, an Eastern European tourist shows off a batik print of a giraffe on rough fabric to no one in particular, inserting nature and the exotic into the urban environment. Onlookers post images on instagram.

In recalling 14th Street of 2014, one new feature that stands out is the hoverboard. Can we assume they are being handed out by banks and Duane Reades? And do the people riding them know that they’re not actually “hovering”? Then again, having walked twice the span of 14th Street by this point, I couldn’t help but recognize the hoverboard as a boon to the promeneurs solitaires of the future, and will insert a plug here that Ed & co. think to provide them for thinkers-in-residence in future years.

Unknown human and likely undercover cop on a “hoverboard.”

Meanwhile, back in Union Square, Dutch artists Marieke Warmelink & Domenique Himmelschbach de Vries who had graced us with their performance in 2014 were back, offering one hour of free help through their embassy of good will.

Marieke Warmelink & Domenique Himmelschbach de Vrie, Embassy of Good Will, One Hour of Free Help.

I notice an empty chess table and am drawn to a memory of the artist Clark Stoekely, who in 2014 set up a chess set and enacted Chess Draw with passersby (though the performance also touched the social fabric of the chessplayers, one of whom decided he would play a day of free matches — usually games are paid at $5 a match — as a gift to the public in parallel with Stoekely’s performance.)

2014 FREE artist Clark Stoeckley plays Chess/Draw with AiOP’s Claire Demere.

Further along 14th Street, Tomashi Jackson’s moving portraits of three women who died after physical encounters with the police look out from the framing shop. The faces of the subjects, Tanisha Anderson (died Nov. 13, 2014, age 37 Cleveland, Ohio), Alberta Spruill (died May 16, 2003, age 57 New York City), and Alesia Thomas (died July 22, 2013, age 35 Los Angeles) are painstakingly rendered and then removed, the artist’s body providing the “key color” through her performance. At the same time, Jackson’s work asks us to “recall” the dead, both as they were when they lived and before they became victims, lest we forget that the incredible abuses of power that brought about their deaths are still at work in communities as diverse as Cleveland, New York, and Los Angeles, or anywhere the police act with impunity.

Tomashi Jackson, Untitled (CMYMe) (Alesia, Alberta, Tanisha, and Me), 2015.

Beneath the Highline, I encounter Matej Vakula and Ashley Clark presenting their new and improved Materials for Public Space cart. Always a fan of “cart art,” I stopped to talk with the pair and learn about the citizen science workshops they were leading which was accompanied this year by a public discussion they had hosted considering the future of public space as a response to the Highline’s current dominance in the global imaginary. (All cities seem to want their own Highline these days.) Unfortunately for the Highline, where bikes are not allowed and cart-art has no haven, the cart had to hang out downstairs on the still mostly free and less-regulated street. The conversation invited contributions by urban planners, designers, artists, community activists and even a member of the Highline’s public outreach staff, material from which will be published in a future iteration of Vakula’s Manuals for Public Space.

AIOP 2014/2015 Artist Matej Vakula with Ashley Clark, demonstrating a citizen science tool designed by group The Public Lab beneath the Highline. Part of Vakula’s ongoing project Materials for Public Space.

Matej Vakula’s community-built Newtown Creek model from AiOP 2014.

Expecting to see Flux Flags, the waterfront installation by Milja Havas and Johannes Rantapuska, I headed to the water’s edge on the West end of 14th Street. Instead, the zone was blocked off, and a pile driving machine was seemingly building a new pier (or maybe it’s Diane von Furstenberg and Barry Diller’s new island park?) No Flux Flags this year, it seemed, but perhaps the artists had put up some of that striking orange netting in collaboration with the coastal engineers? In the end it wasn’t so important – the piece had existed once, and continues to exist through their efforts to reproduce it.

So ended my trip through the flux of the city, brought to its logical conclusion at the end of 14th Street, just in time to catch the first and last sunset of that particular day in October.

Havas and Rantapuska with Flux Flags in 2014 shortly after the install.